Bina and I visited three places during our Tanzanian safari: the Tarangire and Serengeti national parks and the Ngorongoro Crater. The first two consist of mostly open, flat grasslands — what you might think of as prairie or steppe country. Ngorongoro also features grassland, but confined within a volcano crater, hence the name.

More precisely, the Ngorongoro Crater is a caldera, which is a kind of sinkhole created in the aftermath of a volcanic eruption. The force of the magma rising to the top undermines the rock crust above, causing it to subside into the magma chamber. This creates a cauldron-like dip in the earth.

The one at Ngorongoro emerged about three million years ago and covers nearly 260 square kilometers (162 square miles). Featuring both salt and freshwater lakes, it attracts an incredible diversity of animals and birds.

During our two-day visit, we stayed in the Ngorongoro Serena Safari Lodge, which perches on the crater rim, like most hotels in the area. On our first morning there, we woke up to find a water buck sitting right outside our veranda.

The floor of the caldera is 610 meters (2,000 feet) below the rim, the sun shimmering off its dominant feature, Lake Magadi. Maasai tribespeople, who make their living mostly by herding cows, lived within the crater until earlier this year, when the government relocated them to a settlement about 600 km away. Many others, however, continue to inhabit villages surrounding the crater rim.

To get into the crater itself, our guide Hassani drove us down a steep paved road. The paved road ends at the crater floor, where we experienced rutted, dusty lanes characteristic of Tanzanian nature parks — a bumpety-bump experience Hassani termed the “African massage.”

Our first stop was a wash room located next to a swamp-like watering hole. Here we joined a long line of other safari jeeps packed with tourists gawking at our first nature drama of the day: a buffalo in a standoff with two lionesses and their cubs. The buffalo was standing in the water, his attention riveted by the predators.

We expected a major confrontation but the lions soon retreated to settle down in the grass nearby. Hassani surmised that these lions, who can go up to a week without food, had probably eaten recently. “They’re more interested in protecting their cubs. The buffalo know they’re really in trouble when the lions get low in the grass and start creeping up to them.”

Supporting an estimated 25,000 large mammals, Ngorongoro Crater offers abundant food opportunities for predators. About 100 lions live there permanently, the densest population in the world. Other mammals include wildebeest, zebras, Thomson and Grant gazelles, elephants, warthogs, hyenas, hippos, rhinos and serval cats.

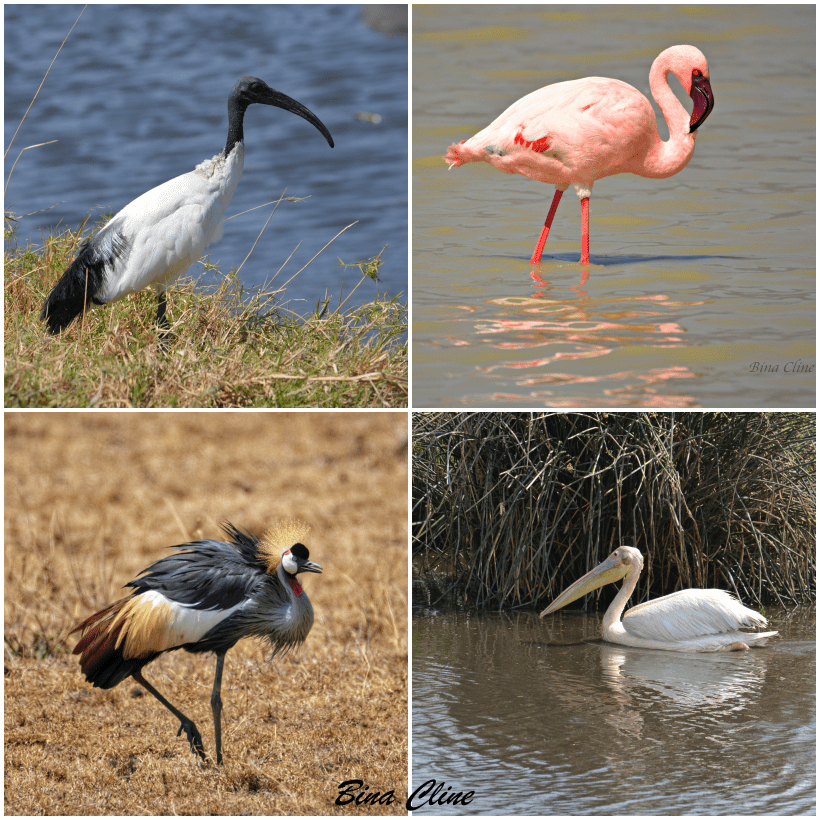

In addition to mammals, Ngorongoro is noted for its 500 species of birds, both resident and migratory. Coming from the Portuguese Algarve, where Greater Flamingos are abundant in the salt pans, we were delighted to find thousands of both Lesser and Greater Flamingos in Lake Magadi, which is salty because it sits on a bed of alkaline volcanic ash. The flamingos feed on dead algae in the shallow lake.

Other sea birds in the crater include the Sacred Ibis, Gray Heron, Great White Pelican and Gray-crowned Crane.

Other parts of the Ngorongoro Crater feature smaller freshwater pools and ponds, fed by streams coming down from the crater rim. Our stopping points during the day included a “hippo pool,” where a large herd of these semi-aquatic mammals spend their day soaking to keep the sun off their sensitive hides. We even got a chance to watch a hippo family emerge from one pool and trudge over to another.

Our first day in Ngorongoro failed to yield a good sighting of a black rhinoceros, which is still considered an endangered species. Poachers had reduced their numbers to 2,500 by the mid-1990s. While a worldwide crackdown on the ivory trade sparked a comeback, only 5,600 can be found in Africa today.

Nearly 30 of these black rhinos live in the crater. Most of them congregate near a research and preservation facility maintained by the government, with access blocked to tourist jeeps. In the late afternoon, other drivers reported a spotting near an old quarry, some distance away. Hassani raced to the spot, only to discover the beast snoozing away in some very distant grass that we could not reach, safari jeeps being restricted to the roads. That left us with just one more day to try again.

That evening, our 35th wedding anniversary, the Ngorongoro Serena lodge prepared for us a special lamb dinner on an outside terrace, which they had decorated with red flowers and green ribbons, a white tablecloth and candles. We were assigned a waitress to serve us exclusively and most of the dining room and kitchen staff came out at the end to sing to us and serve a cake. While Bina and I have traveled widely around the world, we never found better hospitality than during this safari trip in Tanzania!

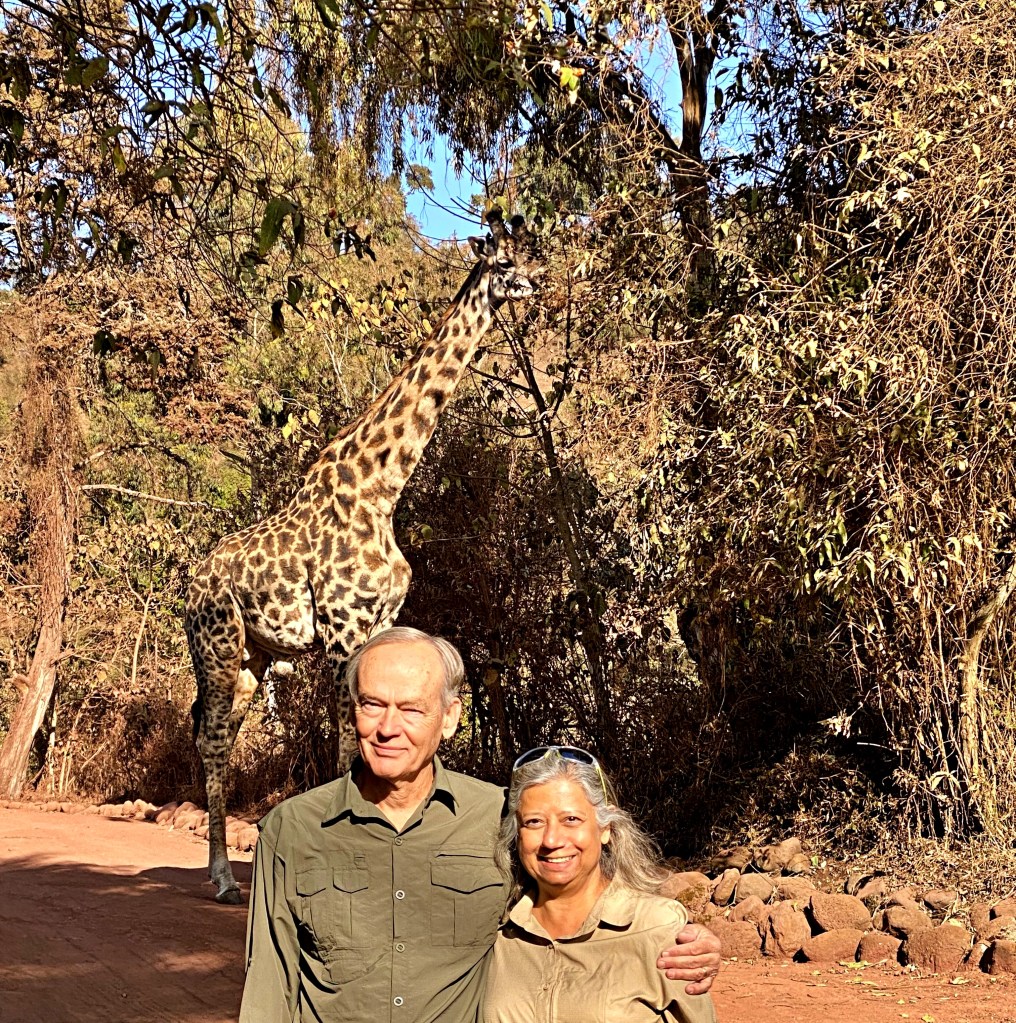

The next morning, upon leaving the hotel, we had another nice surprise: a giraffe grazing on the tops of the acacia trees in the parking lot. Giraffes are abundant on the crater rim but avoid the caldera itself because their long necks throw them off balance during the steep descent.

Returning to the crater floor, we found another drama near the wash room/watering hole. The lionesses, still lazing around, were eyeing with interest a family of approaching warthogs. Most people here refer to warthogs as “pumbaas,” referencing the character in The Lion King.

Catching a scent of the lions, the leading male pumbaa stopped dead in his tracks. After considering the situation, he resumed his walk, albeit in a wider arc that avoided the watering hole. The four members of his family dutifully trotted after him.

Later that morning, we checked again for the rhino at the quarry but no luck: it was still hiding in the grass. Around noon, we followed other jeeps to an area near Magadi Lake. Another rhino had been spotted here. It was more than six football fields away, by Hassani’s calculation.

At that extreme range, we couldn’t make out much more through our binoculars than a dark hump in the grass. “This rhino is more likely to get up when the sun starts going down and it gets cooler,” Hassani said hopefully.

So, we went on to find other photo opportunities, such as the Little Bee-eaters, which was ironic for us. Bee-eaters do frequent the Portuguese Algarve, where we live, but we had never been able to spot one. We had to travel 6,000 km to Tanzania to accomplish that!

It was nearly 5 p.m. when the radio chatter suddenly came alive again. The rhino near the lake had risen to its feet! Being several kilometers away, Hassani told us to hold on and took off like a madman, speedometer clocking 60 kmh, giving Bina and me a vigorous African massage in the back seats. Not even a lion lounging in the middle of the road could detain us; edging gingerly around him, Hassani resumed full speed ahead to the lake.

With the naked eye, we could still make out very little at this distance. Fortunately, my Nikon Coolpix P900, with its 2,000 mm zoom range, could just capture the rhino’s outline.

It was now a quarter past five and Hassani had only 15 minutes to get out of the crater before the rangers locked the gate. Asking them to re-open it would cost us a $100 fine. Fortunately, Hassani managed to slip through the open gate right at 5:30, no ranger yet in sight.

Our two-day safari in the Ngorongoro Crater had ended on a good note. We were now looking forward to our next adventure the following day — the Serengeti.

Fantastic. Felt like I was on a safari myself! Is that a bee in the bee eater’s mouth? You go, Bina. Great narrative to go with the photos. Thank you both.

LikeLike

Great post. Thanks!

LikeLike

Bina and Ken, Thanks for sharing your beautiful adventures with your friends who are unable to make the trip. You both look so happy in your photos. I can’t wait to hear about your next trip. Jan.

LikeLike

Loved reading every word. Enjoy following your adventures!!

LikeLike

Bina and Ken,

I’m enjoying reading about your experience. We visited the same parks 17 years ago over Christmas and New Year.

I don’t remember any water in the crater, perhaps it was much drier and or my recall is fuzzy. I do remember getting a close look at black rhino there (we’d seen several in Kenya before getting to Tanzania).

We witnessed a huge territorial lion fight on NY’s eve in the Serengeti. A year or so later I tried to find someone who had filmed it (via a Google search) and it turned out that someone from Seattle had (we lived on Bainbridge Island—a stone’s through from the guy).

He shared it with us. There were a couple of dozen lions in each group. Quite an experience!

https://photos.google.com/share/AF1QipN8DLGrA0xkuwuXSqlBAlYpKuAIWsEdwtJ-Boo_bg0_7DQsAUIndJ7SQCb1zgxz7A/photo/AF1QipOs_3k1ipXwF4CIRRPJ0FiG1vfDH0At8poQIise?key=ZE9OVURkR05Mck54REdVckphQjRMWm5adlBqenNB

I would love to go back some day, but it may not be in the cards for me. I’m happy that we got to spend two weeks and had incredible experiences as you two have. We were there for my 60th birthday and left Seattle on our 38th wedding anniversary!

We too, experienced wonderful hospitality. I hadn’t thought about it, but it may have been the best in our travel experiences also.

Best,

collie

LikeLike

Thanks, Clint. Yes that is a bee in the bee eater’s mouth. I’m going to change the caption to make that more obvious to readers!

LikeLike

Thanks for your kind remarks, Jan. It was a great trip for us.

LikeLike

Thanks for the link to that fantastic video, Collie! I wouldn’t have wanted to be outside the jeep during that episode. Glad you enjoyed the reminder of your own good times in Tanzania.

LikeLike

Great summary and photos, Ken and Bina! Keep them coming.

LikeLike

Thanks, Lucy.

LikeLike

Wh

LikeLike