From the Rhine River to the Atlantic coast of Portugal, Roman ruins are common across Europe. Rome, Pompeii, the Ponte du Gard and Hadrian’s Wall come immediately to mind. Fortunately for those of us living in the Algarve, some remarkable examples can also be found just a short drive away — such as Mérida, Rome’s crown jewel on the Iberian Peninsula.

For Bina and me, who live in Tavira, it is only a three-and-a-half hour drive. And it’s four-lane motorway all the way: east to Seville and then north to Mérida. Once we got clear of the urban congestion around Seville, the view from the car window of Spain’s Extremadura plateau included an occasional medieval castle or fortress nestling on a hilltop.

Mérida introduces itself as a modern, sprawling suburb until you cross the Guadiana River and enter the core of the old city, which includes what the Romans knew as “Augusta Emerita.” Now designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, this area includes some of the best preserved Roman ruins in the world. I think of it as a mini-Rome, because you’ve got most everything you can find in Rome — Colosseum, circus, theatres, temples and aqueducts — albeit on a smaller scale. It also houses a world-class museum of Roman artefacts.

Why did the Romans build their city here? Extremadura today is one of the poorest regions in Spain, dependent on agriculture and and mining, featuring harsh, often scorching summers. But the location had strategic value, with road links to Roman cities such as Ebora Liberalitas Julia (Evora), Olisippo (Lisbon), Hispalis (Seville), Corduba (Córdoba) and Teletum (Toledo). It also featured plenty of farm land, ideal for the Roman purpose of establishing a colonia (colony) for some of their legionaries.

During the Roman Republic, which lacked a full-time army, settlers in a colonia would have comprised ordinary citizens migrating to a frontier region such as Spain to “claim” it for Rome and begin propagating Latin language and culture. The empire, however, needed to reward its retired professional soldiers with cheap land. The Emperor Augustus founded Augusta Emerita in 25 B.C. to help veterans of several legions who had participated in hard-fought campaigns to complete the conquest of Spain. It soon became the capital of Lusitania Province, which covered much of southern Iberia, including the Algarve.

The Airbnb that Bina and I rented for four days was well situated for exploring Mérida’s old town. Located in a residential area on Calle Poeta Deciano, we were only three blocks from the main ticket office for all the Roman sites in Augusta Emerita. From that facility, we could enter directly into the enclosure containing the amphitheatre and theatre.

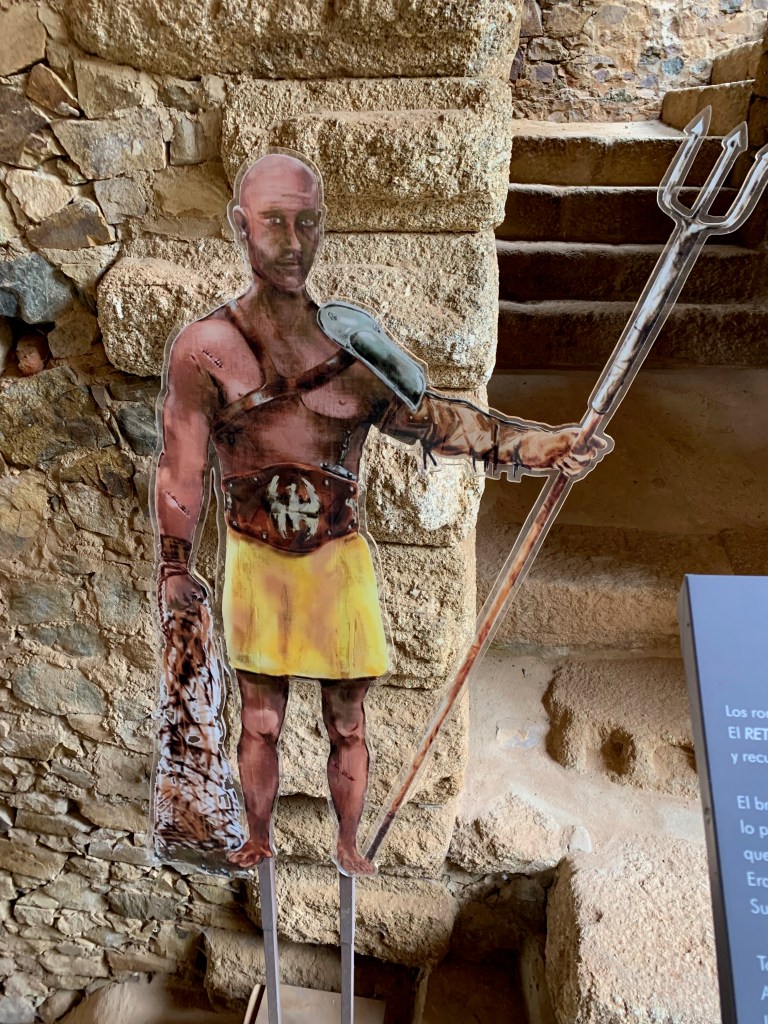

The amphitheatre, a smaller version of the Colosseum in Rome, was designed to hold about 15,000 spectators, gladiator fights being a top-drawer entertainment. As you walk through the dark tunnels underneath the stone bleachers, you can view poster boards illustrating the various categories of gladiator and their equipment. The Retiarius, for example, is the guy who tries to ensnare you in his net and then poke you to death with his pitchfork. The Secutor is more heavily armored, with helmut, shield and spear. Would you rather have all that protection or be light on your feet, like the Retiarius?

A short walk away from the amphitheatre is the theatre, which offered more refined entertainment. This structure was erected in the years 16 to 15 B.C. and remains in remarkably good condition, thanks to modern renovations. You can sit up in the bleachers and get some sense of what it would have been like to watch a comedy by Plautus or one of the Greek tragedies. If you’ve ever seen A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, by the way, you’ve seen a Plautus comedy.

Adjacent to the park complex that houses the amphitheatre and theatre you’ll find the “Casa Romana del Anfiteatro,” ruins of a villa notable for the elegance of its mosaic floors and the beauty of its central courtyard and garden. The Roman aristocracy lived a good life in the first few centuries of the empire, before the disruptions of civil war and barbarian invasion.

This aspect of Roman life is reinforced by another site, the “Casa del Mitreo,” which is located within its own gated park a 10-minute walk southwest of the ticket office, bordering the N-630 highway. This comprises another aristocratic villa with the characteristic interior garden framed by a peristyle walkway. It’s best known for the Cosmogonic mosaic discovered on one of its floors, an allegorical representation of the Roman myth of the origins of the cosmos.

The same park that contains the Mitreo house includes tombs and exhibits related to Roman funeral practices. This can be a somber walk as you contemplate how people tended to die much younger in those times (in their 30s, on average) and how rituals for mourning the dead are important in all human cultures. Romans generally cremated their dead in the early period of the empire, although inhumation (earthen burial) came back into practice in later imperial and Christian times.

As you exit the Mitreo park, it might be worthwhile to cross the street and take a quick look at the municipal bullfighting ring. Posters and photos of prominent matadors from the last century are displayed in the arcade. Then, it’s a stroll to the northwest along Calle Oviedo to reach the Puente Romano (Roman Bridge) over the Guadiana.

Still in use for pedestrians, this is one of the longest bridges remaining from Antiquity, with 60 arches spanning 721 meters. I would rank this bridge and the theatre as the two visual highlights of Roman Mérida. The bridge is best enjoyed at dusk, when the softer light makes for stunning photographs. One caveat: although the foundations of the bridge date from the first century, it has been repaired many times since, most notably after a flood in 1603. Much of what you see today consists of these later additions.

Continuing along the right bank of the Guadiana, we soon come to another spectacular sight, the Acueducto de los Milagros, or Aqueduct of the Miracles, so labeled by the locals out of sheer awe at how something this large had survived so long. This massive piece of hydraulic engineering was built in the first century to bring water to Augusta Emerita from Proserpina Dam, which is located five miles west of the city. That earthen dam with a retaining wall is still used by modern Mérida.

From the aqueduct, it’s time to reverse direction and head southeast back into the heart of Mérida’s old town. There’s a lot to see here, including charming restaurants and tapas bars on pedestrian-only squares and streets. But we’re going to focus on three more Roman sites: the Temple of Diana, the Forum and the Trajan arch. These are all grouped in the center of town within easy walking distance of each other.

The temple is easily the most scenic of the three. Most of the columns, with some lintels and pediment still attached, have survived to the present day because they were incorporated into a palace belonging to an aristocratic family in the 16th century. A restored section of the palace stands behind the temple. You can walk through the rooms and view some exhibits related to the complex.

The temple, however, has nothing to do with Diana, the Roman goddess of the hunt. It was actually erected to provide a place to worship/honor the imperial family. The name “Temple of Diana” got erroneously attached in the 17th century and has stuck ever since.

A few blocks away from the temple stand some ruins identified on Google Maps as the “portico” of the Roman forum. This consists of a few standing columns and some statues located in niches in a brick wall running parallel to the columns. It’s worth a quick look. The Temple of Diana and portico were both part of the Forum of Colonia, the main center for civic activities in Augusta Emerita.

The final Roman monument in the center of town is the “arch of Trajan,” which actually has nothing to do with the Spanish-born emperor who extended the empire to its fullest extent in the 2nd century. It’s basically just a gate and likely served as the monumental entrance to a second, less important forum located in the city. We can’t know its purpose for sure because the marble facade of the arch, which probably featured commemorative inscriptions, has long since disappeared.

Having viewed all the sites related to Augusta Emerita’s build-out in the first century, we can turn our attention to a structure erected in the city’s declining years, in the 4th century. This is the Basilica of Santa Eulalia. What we see today is a 13th century structure constructed on the remains of a 4th century church that was destroyed by the Moors when they conquered the city in 713 A.D.

The church honors St. Eulalia, a Christian teenaged girl who was tortured and burned at the stake for her faith in 304 A.D. The basilica is notable for the Roman era tombs found under its foundations. Symbolically, for us, this visit completes our journey through the history of Augusta Emerita — from its foundation in the first century to its conquest by the Moors in the seventh. After that time, we’re dealing with an Islamic city — and there’s a well-preserved 9th century Moorish fortress/palace by the Roman bridge — and then Spanish/Christian Mérida after the 12th century.

I did leave one important monument out of this account: the Circus, or chariot racetrack. Since it’s located outside the old town, Bina and I had saved it for the last day of our trip. Somehow, we missed the turn-off when driving back to Tavira, so we’ll have to check it out on a subsequent visit. As an FYI: the interpretation center for the Circus, which is where you begin your visit, is located in the park adjacent to Avenida Juan Carlos I. It’s worth the trip because this is considered one of the best-preserved racetracks remaining from Roman times.

Finally, no visit to Roman Mérida would be complete without spending several hours, at least, in the National Museum of Roman Art. This cavernous box of a building, right across from the main ticket office, houses a fabulous collection of Roman mosaics, wall paintings, statuary and archaeological relics, with commentary in both Spanish and English. It’s also notable for being built across an actual Roman road, part of which remains in perfectly preserved condition; you can almost imagine yourself setting off one sunny day in the 2nd century on a walk to Córdoba.

Note: The walking tour described above could possibly be accomplished in one full day, but two would be required to cover everything without rushing around. Bina and I spent three days in Mérida and one in nearby Badajoz, an hour’s drive to the west, which boasts a magnificent Islamic citadel overlooking the city and a 13th century cathedral. If you like history, Extremadura is your kind of place.

I’m ignorant about Roman times in Spain. This post is a very pleasant way to get a little insight into that time and place. Thanks.

LikeLike

Thanks, Clint.

LikeLike

This is a great summary and I so appreciate your insights. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thanks, anjopico.

LikeLike

Great post! Makes us want to visit soon!

LikeLike

Thanks, Mark. Hope you can do that!

LikeLike

Hi Bina and Ken! Ken, the writer, keeps me interested with his wonderful descriptions! When I have time, I want to look on-line for more pictures of the ruins! It’s so surprising how preserved some are!. It must have been so magnificent for its day! I wish I could be there to see it! Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

Thanks, Jan. Glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLike