Bina will always remember our morning flight from San Cristóbal to Santa Cruz because she got to sit in the co-pilot’s seat.

Our plane was a propeller-driven Piper Seneca II that technically only holds four passengers. But ESAV Airlines, which styles itself as an “air taxi,” offers customers the co-pilot’s seat as an option for an extra fee. In this case, because only two couples had signed up for the flight (us and some young Swedes) they let Bina have the co-pilot’s seat for no additional payment.

“As someone who had seriously thought about taking flying lessons when I was younger,” she said, “this was a dream come true!”

After a fairly smooth 45-minute journey, we landed on Baltra Island, which is adjacent to the much larger Santa Cruz. During World War II, the Americans built an air force base here that the Ecuadorian government converted into a civilian airport, the largest in the Galapagos.

Getting from the airport to Santa Cruz’s main town of Puerto Ayora is a bit involved, requiring a ferry across the straits between Baltra and Santa Cruz and then a drive across the main island, which takes about an hour. Like San Cristóbal, Santa Cruz features a scrubby, desert-like coastline with green and wet highlands in the middle.

To get the most out of this drive as possible, we had hired a driver/guide named Wilson, who took us to some scenic highland locations along the way. Two calderas, known as Los Gemeles (the Twins), provided our first stop. Like Junco Lagoon on San Cristóbal, these are large depressions in a foggy rainforest, just no Frigatebirds swooshing about, since the holes are dry.

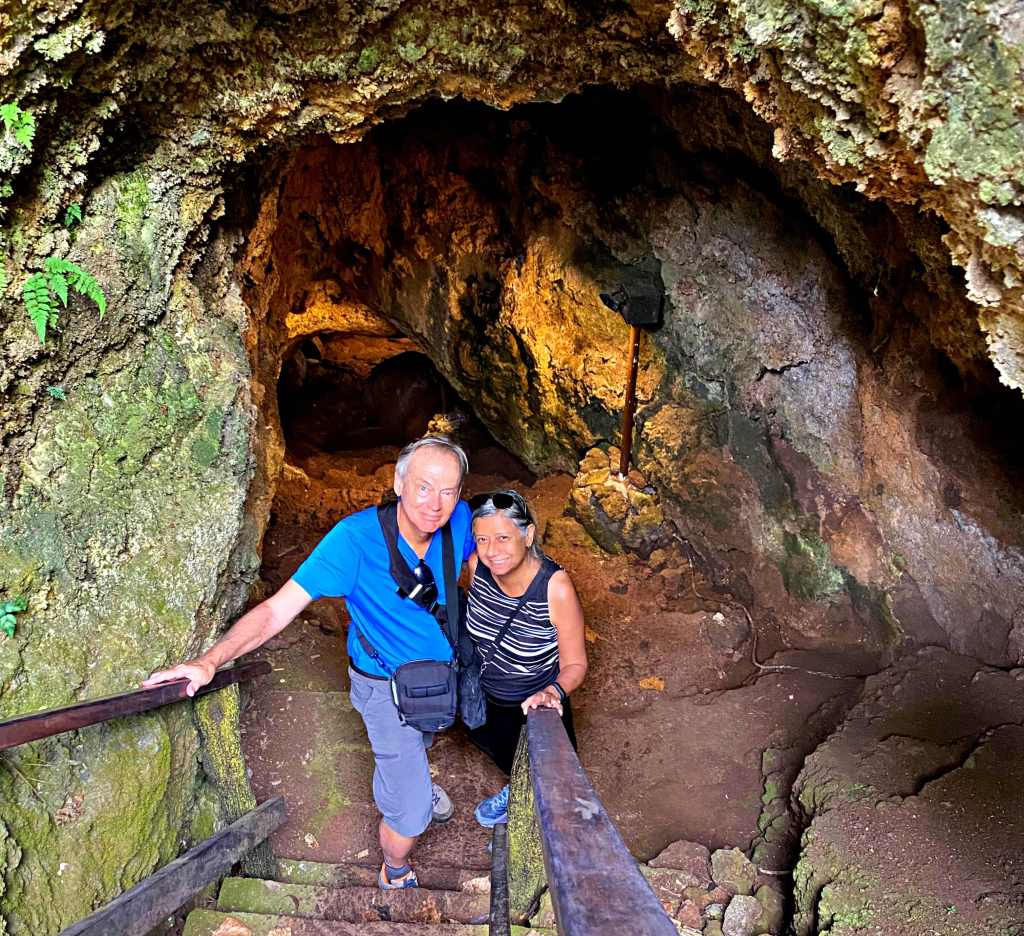

Then on to the Lava Tunnels. Originally created in the black volcanic rock by natural forces, the government had enhanced one of them with some additional clearing and electric lighting so that you could walk through it, except for one narrow passage that requires you to crawl on your hands and knees.

Next, we had a pre-arranged stop at Rancho Primicias, a private ranch whose ponds attract lots of giant tortoises. The guide who took us around the grounds said these creatures can live past 100 if they make it past age five, after which they face no natural predators. Before that age, Frigatebirds and wild pigs can be a lethal threat.

After a quick lunch at Ranchos Primicias’ cafe, Wilson took us to our final stop before reaching our lodging in Puerto Ayora. This was a mountain called Cerro Crocker, where Wilson spotted some birds for us, including a Dark-billed Cuckoo. He also found Bina some bushes featuring ice cream beans (scientifically, Inga Edulis), which she used to love eating when they became available in the markets in Costa Rica. Covered with a whitish fur, these sweet-tasting beans are native to South and Central America.

We liked Wilson so much that we hired him for another excursion a few days later, although this one ran into some weather issues. We had planned to return to Cerro Crocker and hike further into the hills to Media Luna (half moon), a half-collapsed caldera known for its birding opportunities (Petrels and Rails).

Wilson texted us at 9 a.m., just before our scheduled pickup, to say the highlands were drizzly that morning. We decided to go anyway — hoping the drizzle might end — but found Cerro Crocker a muddy mess. Okay, let’s go back to town and see if the situation improves by 2 p.m.

By then, the drizzle had stopped, although the mud remained. That’s the trouble with a rainforest: trails take a long time to dry in all that fog. We tried to hike up to Media Luna but the trail proved too slippery and we only saw the usual Darwin Finches along the way.

Probably as a compensation for this disappointment, Wilson then drove us to Cerro Mesa, a mountain near Puerto Ayora that offered spectacular views of the coast. We could also see Pikaia Lodge, the most exclusive resort on the island, which had just hosted a meeting of the presidents of Ecuador and Columbia. Rooms here go for thousands of dollars a night, but at least it’s “sustainable luxury,” as the hotel assures us.

Aside from these excursions, the rest of our stay on Santa Cruz took place within the confines of Puerto Ayora, whose malecón (waterfront esplanade) provides a great walking area, where Bina and I could hang around the piers and jetties taking photos of birds, iguanas and sea lions.

At the northeastern end of the malecón, we visited the Charles Darwin Research Station, which conducts biological research in the Galapagos under the auspices of an international foundation. A small exhibit hall showcases projects underway to protect wildlife on the islands.

A key finding for us was the fragility of the islands’ ecosystem. For example, 17 of the 28 birds species endemic to at least one island in the Galapagos have disappeared since the 19th century. Of the Mangrove Finches, currently the one most endangered, only about 100 remain.

The Ecuadorian government, according to all its literature and pronouncements, is working hard to preserve as much of the islands’ pristine nature as possible. But the proliferation of building cranes and unfinished concrete foundations we saw in the major towns made us wonder about the continuing influx of people from the mainland, who are drawn by the booming tourism and fishing industry.

The population of the Galapagos is growing by 6.4% a year, higher than Ecuador’s own 2.1%. With 97% of the land area reserved as national park, everyone crowds into the remaining 3%, which transforms former laid-back villages into bustling towns. “That’s the main thing people here talk about,” a waitress in Puerto Ayora told us, noting that locals no longer feel as close to their neighbours. They also worry about the mainland’s high crime rate eventually migrating over to the Galapagos.

But for now, at least, the archipelago remains one of the safest tourist destinations in South America.

Great job. Wonderful, relevant photos!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Clint. Bina works hard on those photos!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this wonderful travel report with such great photos. It makes me want to visit this wonderful part of the world myself.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Anonymous. We’re glad you enjoyed the article and hope that you have the opportunity to do a similar trip yourself.

LikeLike