For us, traveling between Vietnam and Singapore, Malaysia constituted a mid point in the Southeast Asian wealth index: some notches below Singapore, but with a GDP per-capita three times that of Vietnam. English is also widely spoken here, due to Malaysia’s history as a former British colony (1826-1957).

We focused our visit on Penang Island, just off the country’s northwestern coast. The English established a trading port here in 1786, which grew into a major center for the export of tin and rubber from the mainland by the late 19th century. This colonial history is on display in the restored parts of George Town, the island’s major urban area, which received a UNESCO World Heritage designation in 2008.

Our guide to George Town was “Jeffrey,” a cheerful and talkative 62-year old man of Chinese origin, an ethnic background that proved helpful for our tour. Chinese immigrants began arriving here in the 18th century and still constitute 56% of the island’s population, with the rest being Malay and Indian. (Malays, of course, dominate on the mainland proper, just across the Malacca Strait.) This gives Penang culture a strong Chinese flavor.

Jeffrey began by driving us to the waterfront area of George Town, where the British had placed their major military structures (Fort Cornwallis) and government buildings. As in Singapore, British rule provided an protected neutral ground for Penang’s diverse nationalities to interact and trade with each other away from the political conflicts of neighboring sultans.

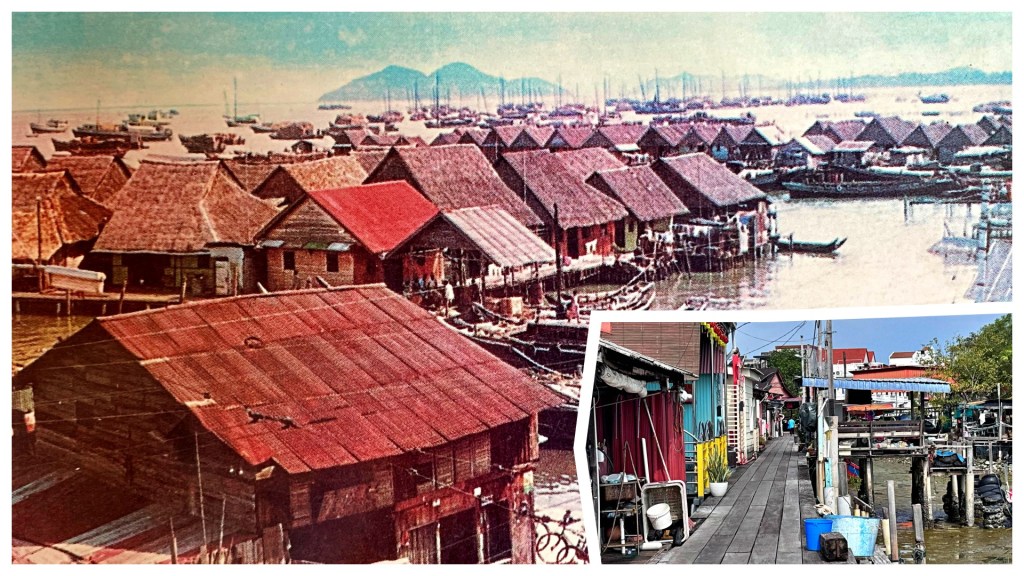

For the Chinese experience, we visited Lim Jetty, a series of wooden platforms with houses stretching out into the bay in which people still live. In colonial times, George Town had numerous such floating villages, known as “clan jetties,” which provided cheap lodging to Chinese immigrants. Only seven remain today. Most tourists gravitate to Chew Jetty but Jeffrey preferred Lim as it is less commercialized and more authentic.

The word “clan” requires some explanation. In a Chinese context, the word can be likened to “tribe,” since members are connected by family and/or regional ties, often common surnames. When immigrants first arrived in Penang, they clustered around people they could trust, either on the jetties or in compounds ashore. Each jetty or compound includes a small shrine, or temple, to the clan’s particular deity or spirit.

The largest such clan temple in Penang today is the Khoo Kongsi (“temple” in Chinese). The Khoo family, which remains prominent in Malaysian business, built a fine museum inside the compound to explain how their clan rose to commercial and political power in the late 19th century. The entire place feels like a miniature fortress, which it was, to a certain extent, since the clans could be fractious with each other (since they competed commercially). A nearby lane is named “Cannon Street” because the police used artillery to quell a major fracas there in 1867.

In walking around the streets of old George Town, we enjoyed the murals painted by Lithuanian artist Ernest Zacharevic. Featuring local street scenes of young people at play, these paintings incorporate physical elements, such as a bicycle or swing, to provide a 3-D effect, so the images jump out at you. They’re guaranteed to elicit a smile.

The images have become so popular that they appear on T-shirts and other souvenirs sold in the sidewalk shops. Since the paint fades over time, Zacharevic, who lives in Penang, spent three weeks restoring them in 2024, 12 years after painting the originals.

Our last stop of the day was Kek Lok Si, a temple complex located near Penang Hill. Erected between 1890 and 1905, and subsequently enhanced by numerous gardens and shrines, this is the largest Chinese Buddhist temple complex in Southeast Asia. The seven-story Ten Thousand Buddhas Pagoda actually incorporates 10,000 alabaster and bronze statues of Buddha, many quite small, of course.

The “wishing ribbons” particulalry caught our attention. Buddhists who visit these temples attach the ribbons, which feature requests for good luck, success and/or happiness, to tree-like hangers. The worshippers hope to solicit the helpful attention of Buddha or some other deity celebrated in that particular temple.

Does it work? After watching another woman doing this, Bina had to give it a try. She picked a few ribbons with wishes that were most meaningful to her and attached them with a short prayer. After all, you can never have enough celestial assistance, can you?

To follow our continuing adventures, please click here.

Good use of history to help us understand what you’re seeing. And nice wrap at the end. Were you this good when you were my editor?

LikeLiked by 1 person

To answer your question, Clint: I hope so! As for the history, it’s funny because I knew nothing about Penang before this trip. I just found the guide’s talk about the clans to be fascinating and researched it when I got home. This was the kind of trip I like, where you go in without preconceptions and find the place to be more interesting than you originally thought. So, I guess you could say this was a truly a voyage of discovery. Anyway, thanks for your kind comments.

LikeLike