For the tourist, Albi is wonderfully compact, the historic area covering only 63 hectares (155 acres). From the Sainte Cécile cathedral, the heart of the old quarter, everything of interest can be reached in a 20-minute walk.

This cathedral is reputed to be the largest brick building in the world, with its bell tower soaring 78 metres (256 ft) above your head. The forbiddingly austere outside walls resemble a fortress more than a church, and there’s a reason for that.

In 1208, Pope Innocent III proclaimed what became known as the Albigensian Crusade as a war against the Cathars, a heretic Christian sect that had taken strong root in this part of southern France. Albi’s name became linked with this tragic episode in French history because of the city’s prominence as a center of Cathar resistance. The war dragged on for 36 years, resulting in the horrific suppression of the Cathars, many of them burned at the stake.

By 1276, after the war, Bernard de Castanet, the new bishop of Albi, was looking for a way to monumentalize the victory of the Catholic church. He decided to build the largest cathedral possible, using brick because it was cheaper than stone, and opting for a fortress-like appearance to communicate the power of the church and French king to withstand heresies such as Catharism. The church took 200 years to complete, but the outside, at least, clearly communicates de Castanet’s message of, don’t mess with us!

Inside, however, you can find the solemn beauty characteristic of a medieval church, with the walls and side chapels bursting with color from paintings, many of them done during the Renaissance. The upper level of the nave includes an organ dating from 1734 (refurbished many times since) whose pipes can blast out a sound sufficient to fill the cathedral’s cavernous interior. The modern classical music played during a public concert Bina and I attended one afternoon was actually so loud that we left after about half an hour. Next time, a little softer Bach, please!

The cathedral, as large as it is, is only part of a complex of buildings that became known as La Cité Episcopale (the Episcopal City). This includes the Palais de la Berbie (“berbie” means “bishop” in the old language of southern France) and the Toulouse-Lautrec Museum. The palace actually predates the cathedral and was built with fortifications to protect Albi’s bishops from potential Cathar attacks. Today, it features a few historical exhibits but is interesting primarily for its lovely garden overlooking the Tarn River.

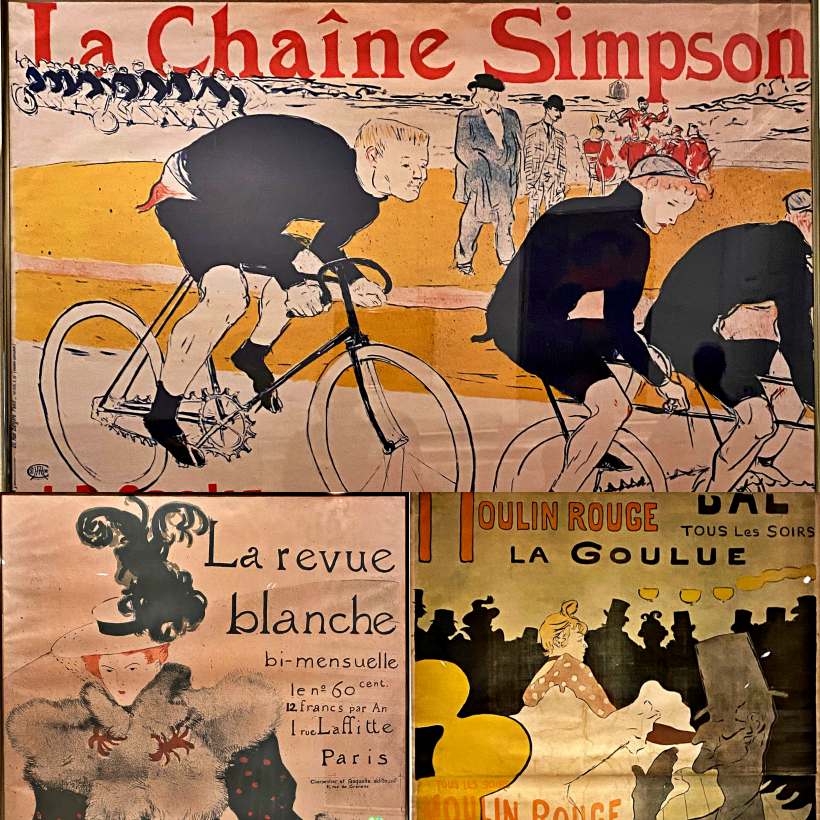

A part of the bishop’s palace is used to house a collection of paintings by Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, who lived part of his life in Albi. The famous artist was born in 1864 at his family’s estate in the small town of Camjac, about 50 km northeast of Albi. The collection, donated to the town by his mother in 1922, mostly covers his early work when he lived in the area.

It was interesting to watch the change in his style from early traditional and academic studies of horses and soldiers to the famous Montmartre posters. This museum did possess some of the nightclub posters but was only exhibiting copies at the time we visited. A placard explained that the originals were being restored because they had been printed on very thin paper with fragile fibers and chemical dyes susceptible to yellowing and discolouration respectively.

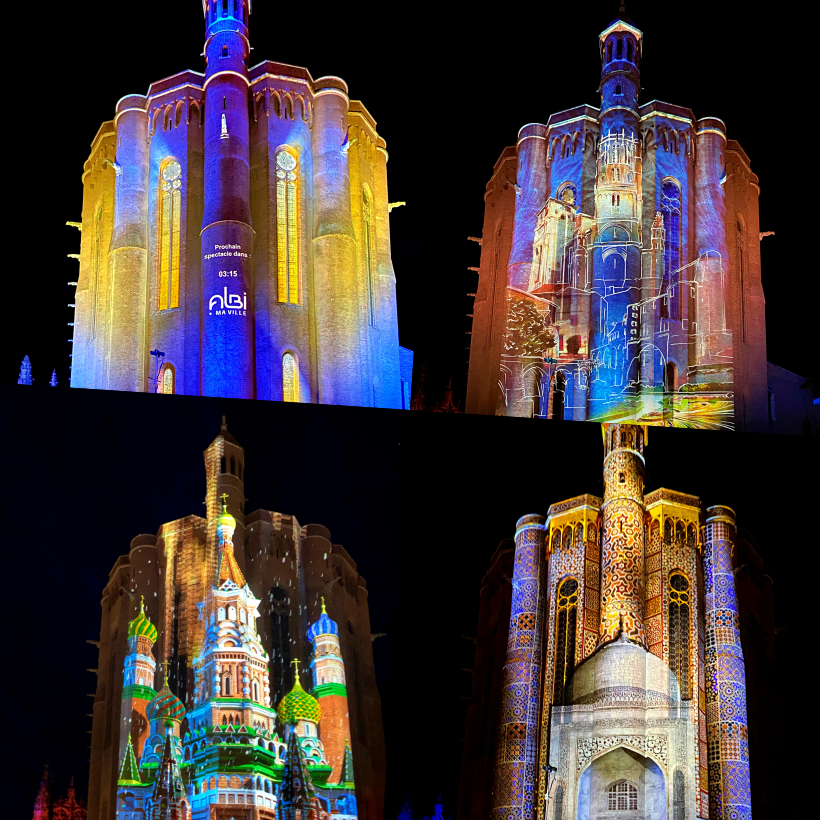

So, after you’ve hit the major spots in the Episcopal City — the cathedral, bishop’s palace and Toulouse-Lautrec Museum, what’s left to do in Albi? Well, you could relax in one of the restaurants and cafes located in the old quarter, or saunter down a narrow lane and venture into some of the numerous tourist shops. On some evenings, the city operates a laser show at the cathedral featuring images of iconic sites around the world.

You can also walk a short distance to the Tarn River and cross the Pont Vieux (“Old Bridge,” built nearly 1,000 years ago) for a great view of the cathedral and palace as well as the brick mills and warehouses lining the river.

Most of these industrial structures derive from Albi’s role in producing woad, a blue dye made from the green Isatis Tinctoria plant. Great fortunes were made in this industry between the 14th and 16th centuries in the triangle of southern France bounded by Toulouse, Albi and Carcassonne. This region became the largest woad producer in the world, earning the name “Pays de Cocagne,” or land of woad balls.

The golden years ended late in the 16th century when woad began losing out to an Asian import, the Indigofera Tinctoria plant, otherwise known as True Indigo, which proved more colorfast than woad. Napoleon tried to revive the industry when a British naval blockade cut off France’s access to indigo, which his army needed for their blue uniforms. But this experiment in “import substitution” did not survive his reign.

With all its historical ambience, today’s Albi is a modern town with modern concerns. One afternoon, we were returning to our hotel — the Ibis Styles, just 15 minutes from the old quarter — when we encountered a protest march. These were mostly anti-vaxxers who resented President Macron’s recent order requiring the EU’s Covid vaccination certificate for entrance into public places. Some of the (mostly middle age) crowd carried signs demanding “Liberte” and “Droits du l’homme” (the rights of Man). I did notice one guy with a red flag picturing Che Guevara.

That’s one side of France, but there’s another … during dinner one night at the Alchimy Restaurant, we were entertained by the “Rocking Billies,” a band comprised of three middle-aged French guys who specialize in American Rockabilly from the 1950s and early ‘60s. Their renditions of songs such as “Johnny B. Goode” and “Pretty Woman” tracked the originals pretty well, albeit with rounded French vowels substituting for country twang.

Not ideal for the romantic dinner we were hoping for — it was Bina’s birthday — but good for the occasional, “I can’t believe they’re playing that!”