Ronda — that’s the Spanish town with the bridge over the gorge, right? True, and the bridge is indeed a magnificent sight. But that’s not all you can see and experience in Ronda, as Bina and I discovered during a two-night visit in January 2024 with our friends Andrew Cousins and Heidi Beck.

From São Bras de Alportel, where we all reside, we took the motorway to Seville, staying one day to see the Alcazar and Plaza de España, and then traveled the two-lane A-374 highway to Ronda the following day.

Ronda is located in Andalusia, roughly two-thirds of the way from Seville to Malaga, in a valley nestled between the Grazalema and Las Nieves mountain ranges. The town, with a population of 35,000, sits on a hill of its own at 739 meters (2,425 ft) above sea level overlooking a nearly vertical gorge that separates it into “old” and “new” quarters.

The old town dates from the Islamic period (7th to 15th centuries) while most of the new was built after the Christians took over in 1485. By American standards, as Bina and I joked, both parts qualify as “old.”

Since the bridge is the center piece for most tourists visiting Ronda, we’ll tackle that first. Three bridges actually span the gorge. The famous one is the Puente Nuevo (New Bridge) at the the very top, completed in 1793; the other two, the Puente Romano (Roman bridge) and Puente Viejo (Old Bridge) are lower down and constructed earlier.

The Puente Romano (also known as the Puente Arabe) dates from the 14th century (Islamic period) and is the farthest down, traversing the Guadalevín River, which flows through the gorge; the Puente Viejo, roughly at mid-level, was built in 1616. Both these bridges leave pedestrians a still-strenuous walk up the hill to reach the new town, which is why work on the Puente Nuevo began in the mid-1730s.

On their first attempt, the builders tried to do this on the cheap with a single-arch design; it collapsed in 1741, killing 50 people. A new architect and builder then took over and got the job done right with the three-arch span we see today. Under the central arch, one can discern a door marking a room once used as a prison. During the 1936-39 Spanish Civil War, both sides allegedly used this structure to torture prisoners and throw them into the gorge below.

Ernest Hemingway, who first came to Ronda as a reporter during the conflict, is said to have used these stories as a model for a scene in his novel For Whom the Bell Tolls in which Nationalist sympathizers are thrown from the cliffs of a fictional village by their Republican captors.

In later visits to Ronda, Hemingway celebrated the town’s love of bullfighting. As he wrote in Death in the Afternoon: “There is one town … to see your first bullfight in if you are only going to see one and that is Ronda … The entire town and as far as you can see in any direction is romantic background.”

Our hotel, the Catalonia Ronda, proved an excellent choice for experiencing that “romantic background.” Our rooms on the third floor, along with the Catalonia’s rooftop bar, actually overlooked the bullring, with a view towards the mountains beyond.

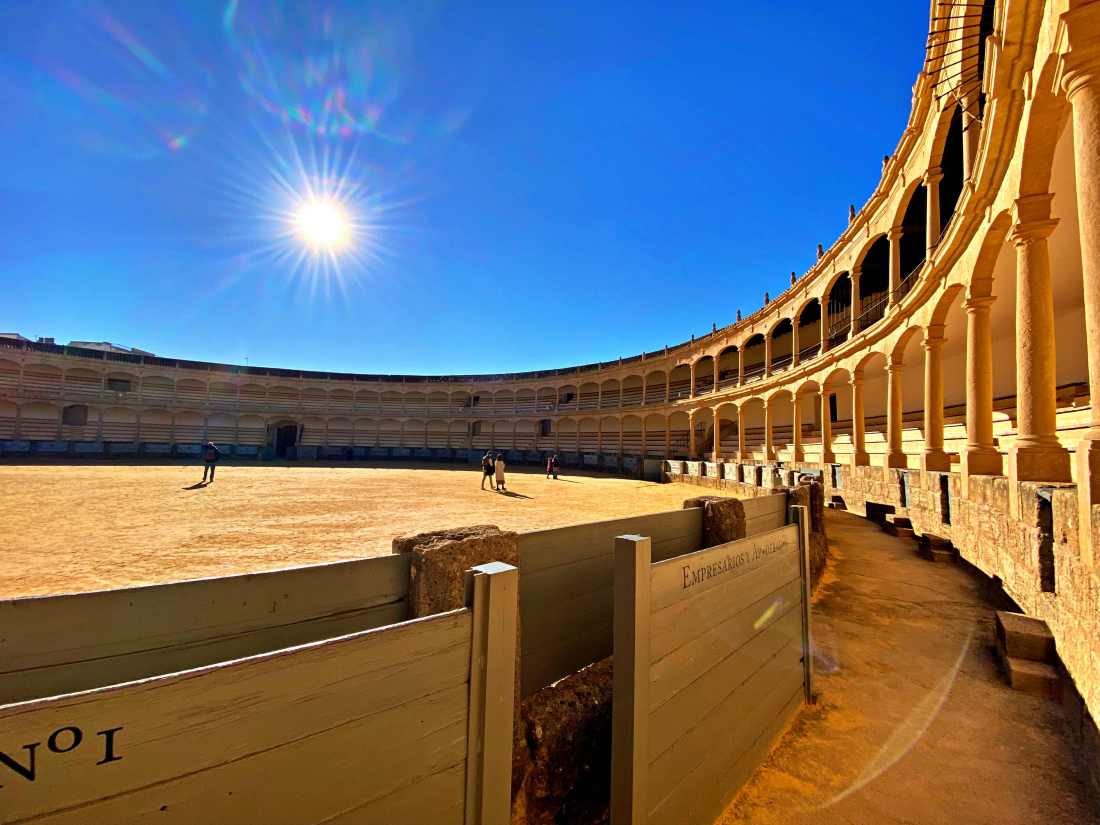

The four of us began our full day in Ronda with a morning visit to the bullring, which proved much more interesting than expected because the complex includes both the arena for bull fighting as well as stables and exercise grounds for an attached “Spanish riding school.”* The history of the two is very much intertwined, as we learned from exhibits in the excellent on-site museum.

The story begins in 1573 with the founding of the Real Maestranza de Caballeria (Royal Order of Cavalry), the first such riding school in Spain. This school continues today as a non-profit organization overseeing its rider training, horse stables and archives. The original mission was to train cavalry to protect the Andalusian frontier from the Moors. This training often involved sparring with bulls, an exercise known as “torreo.”

Over time, torreo gave way to capea, a cheaper, less elitist way of fighting bulls on foot with capes. By the 18th century, bullfighting had become a spectator sport in circular arenas known as “plazas de toros.” Ronda’s plaza, built in 1785 of sandstone, is considered the first to be designed exclusively for this purpose. Bullfights are still held here every year at the end of August/beginning of September during an annual festival commemorating Ronda’s role in the evolution of this sport.

The bullring’s museum includes matador costumes and exhibits related to two of Ronda’s most renowned bullfighting family dynasties, the Romeros from the 18th century and the Ordóñez from the 20th.

Antonio Ordóñez (1932-1998), a top star in the 1950s and early ’60, was befriended by both Hemingway and actor/director Orson Welles, another avid fan of Ronda. Hemingway profiled the bullfighter in The Dangerous Summer, his last published book, while Welles’ remains are interred in a dry well on the Ordónẽz family estate.

Ronda’s plaza de toro and celebrated bridge are located a few blocks from each other on the town’s upper level. To reach the Baños de los Arabes (Arab Baths), another major tourist site, you need to descend to ground level on the eastern side of the old quarter. The walk takes you past the medieval walls, from whose ramparts you can view the surrounding countryside. We saw someone taking their horse through dressage exercises in a distant field.

The baths are in a ruined state but preserved well enough so that you can understand how they functioned, particularly after watching a 10-minute video with shows alternately in Spanish and English. A water wheel device housed in a tower and powered by a donkey served to divert water from an aqueduct into channels beneath the floor, where it was then heated to produce steam, enabling the users to sweat out impurities in their skin.

Scholars have not yet been able to determine exactly when these baths were built; the best guess is late 12th or early 13th century. They remained in use until the Christian conquest of 1485. The town’s Muslim inhabitants were expelled in 1570.

If you want to learn more about Ronda’s Moorish past — which lasted for 700 years — you can visit the Mondragon Palace, which was built in the 14th century by the town’s Islamic rulers and now houses an informative archaeological museum. Exhibits there illustrate how Ronda has been inhabited since Celtic settlers first arrived in the 6th century B.C.

Also worth a stop, in the old quarter just past the famous bridge, is the tiled mural providing an aerial view of Ronda, with approving quotes from the Viajeros Romanticos (Romantic Visitors). These were prominent people, such as American writer Washington Irving and British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, who visited the town in the 19th century. “Ronda is, indeed, one of those places that stands alone. I know of nothing to which it can be compared,” reported Lady Louisa Tenison, the English artist and travel writer, in 1850.

As all four of us can testify, the beauty and romance of Ronda lingers still.

* The term “Spanish Riding School” may be familiar to readers of our blog who read our post on Vienna, where we enjoyed a show by the famous Lipizzaner stallions. Vienna’s Spanish Riding School had its origins in the 16th century, when the Spanish-born Hapsburg Emperor Ferdinand I imported Andalusian horses and riding experts for the imperial stables in Vienna. In those days, Spain was the go-to place in Europe for horse breeding and dressage techniques.