The visit that Bina and I made to Budapest in the summer of 2024 was our first to Eastern Europe. It was about time, since these countries have integrated well into the rest of Europe since escaping Communist control back in 1989.

Budapest was an obvious choice for us, given direct flights from Faro on Ryanair — three and a half hours from the Portuguese Algarve and you’re landing on the plains of Hungary. It also seemed fitting, given our trip to Vienna the previous year. Between 1867 and 1918, Budapest served as the second capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, after Vienna. Most of the great buildings you see there today date from this imperial period of the late 19th/early 20th century, which is similar to Vienna.

The histories of the two cities diverged sharply after World War II, with big impacts on their physical appearances today. Thriving on the western side of the Berlin Wall — Austria is now one of the richest countries in Europe — Vienna can afford to rehab its older buildings until they gleam like new. Budapest had a rougher time during the war — 80% destroyed in house-to-house fighting in 1944 — and then Hungary endured 40 years of tyrannical, penurious Communism.

The city has done a great job restoring its historic quarter since the 1990s, but remains an edgy juxtaposition of 19th century elegance with Soviet Era decrepit. Arriving on the afternoon of June 30, we made the wise decision to do an evening river cruise, when you can see the city at its best. The hour-long voyage, operated by Lagenda Cruises, started at 8:45 p.m. and took us up the Danube to Margaret Island and back, with all the iconic structures outlined in lights.

Two days later, we got an on-the-ground look at that landscape during a morning walking tour with George, an Airbnb Experience guide. We began by taking the M1 metro line to what’s known as “Heroes Square,” which commemorates the founding of Hungary in 896; statues of seven horsemen represent the Magyar tribes that migrated to the Hungarian plains that year from the Ural Mountains. A colonnade behind features other statues of famous leaders in Hungarian history.

Just past Heroes Square, we entered Budapest’s major municipal park, home to a large pond used as a skating rink in the winter; the city’s largest thermal baths (the Széchenyi); and the stunning Vajdahunyad Castle, a kind of Disneyland of Hungarian history. Inside the walls of this “castle” overlooking the pond are reconstructed facades of famous buildings located throughout the country.

As our guide George explained, this entire area — the square and the castle — were designed and built just prior to an international exposition in 1896 that celebrated 1,000 years of Hungary’s existence. The M1 metro itself was constructed expressly to transport international visitors to the park from the hotel district on the Danube (the “M” stands for “Millennium”). The German firm assigned to the project had to move fast, so they kept the tunnel shallow, just under the streets, and used electric rather than diesel trains to eliminate noise and air pollution.

Continuing our adventures with George on the Budapest metro, we also visited the Opera House (built in 1888) and Parliament building (1902). Our visit to the Opera was very brief, but Bina and I came back later in the day to take an English language tour, which enabled us to view the rich ornamentation inside the concert hall and enjoy a mini-concert of arias from Rigoletto, which was on the current program.

The Parliament building, with its Neogothic facade, is probably Budapest’s most famous landmark, and remains the country’s largest building, 122 years after it was first erected. We did not have time to return for a indoor tour, but people who do can view the heavily guarded 11th century Holy Crown of Hungary, a gift from the Byzantine emperor. The crown was stolen by the Germans in World War II but recovered by the Americans and held in Fort Knox until President Jimmy Carter ordered it returned in 1978.

The Parliament building, by the way, is exactly 96 meters high (315 ft.), as is St. Stephen’s Basilica, the city’s main church, which was completed in 1905. That “96,” of course, is no accident given … drum roll, please … the country’s 896 founding date. Bina and I did tour the basilica later, where we were able to view the mummified hand of St. Stephen, Hungary’s first king (c. 975–1038). A terrace along the outside of the cupola offers panoramic views of the city.

Then it was across the river via metro the to the “Buda” side of Budapest. This is a different sort of place, hilly and rocky, while Pest is broad and flat. Traditionally, it’s been where Hungary’s kings erected their fortresses and wealthy folk their villas; the official residences of the prime minister and president stand there today, side by side. Pest, by contrast, has always been a mixed residential and commercial area, where people live, shop and entertain themselves. The two cities were not actually united until 1873.

Buda’s main attractions lie within a fairly compact area known as Castle Hill. With George, we walked past the top three: Buda Castle (once a fortress, now housing two museums); the Fisherman’s Bastion (a nicely restored stretch of walls offering great views of the Danube and Pest); and the 14th century Matthias Church.

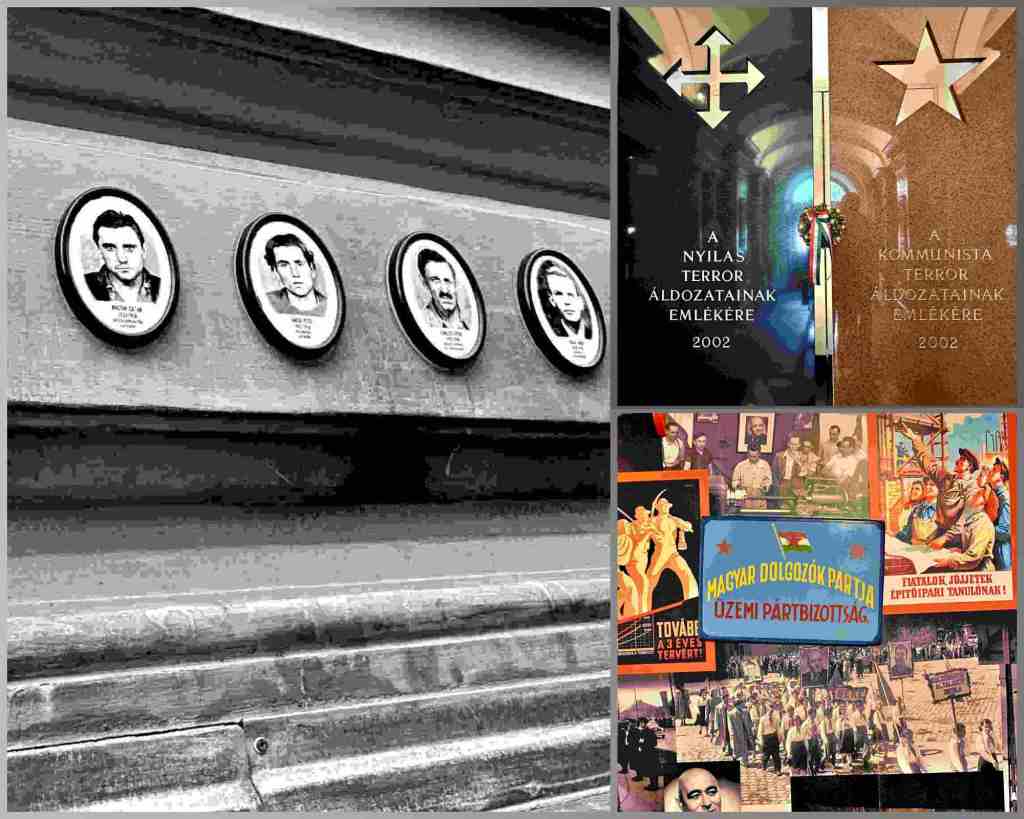

During our walking tour, we learned about some of the darker episodes in Hungary’s recent history and George suggested places to explore that further, which we did the next day. We began with the “Jewish shoes” monument, which is located on the Danube bank close to the Parliament building. This iron sculpture of empty shoes attached to the embankment memorializes the massacre of approximately 20,000 Hungarian Jews by the fascist Arrow Cross militia in the winter of 1944/45. Herded to the river bank to be shot, the victims’ bodies were dumped into the water, leaving their shoes behind to be sold by militia members.

Later that afternoon, we paid a likewise somber visit to the House of Terror, a museum located on Andrássy Ave., just a few blocks from our hotel, the Eurostars Ambassador. In 1944, this building became the headquarters of the Arrow Cross party, which ruled Hungary for about 160 murderous days before Russian troops entered Budapest. After the war, the building was occupied until 1956 by the Communist secret police, with the basement reserved for horrific torture interrogations.

While knowledge of this dark history may be important for understanding elements of modern-day Hungarian politics, it should not obscure how far Budapest has come since the war. Andrássy Avenue, known as the city’s Champs-Elysée for its wide lanes, park-like squares and elegant 19th century buildings, is today an area vibrant with restaurants, shops and bars. With reasonable prices, compared to central Europe, Budapest is a town where visitors flock to enjoy the cuisine and nightlife.

Bina and I learned a lot about the Hungarian cuisine during a cooking class that also featured a young fellow named George. Holding a brown straw shopping bag, George met us near the Danube at the Neogothic entrance to the Nagycsarnok (Great Market Hall), the city’s largest indoor food market.

After a tour of the market’s vendor kiosks, where George purchased chicken and peppers for our upcoming meal, he guided us to his flat about 10 minutes away, which had a large and modern kitchen. Being his only customers that day, we had George’s full attention as we sampled some local wine and hors d’oeuvres, which included pickled vegetables and different types of salami, including venison. Pickling, by the way, is an important element of Hungarian cuisine, harking back to the pre-refrigerator days when no other means of preserving food was available.

We next prepared chicken paprikash, based on his grandmother’s recipe. One key lesson: don’t stint on the amount of papriika you use, both in powdered and creme form. George also showed us how to make spätles (dumplings) from a flour mixture that is poured through a sieve into hot water.

I’m happy to report that we were able to successfully recreate the recipe after we returned home!

Travel Note: While Hungary is a member of the EU (since 2004), it has not yet been admitted to the euro currency zone because of excessive public debt and inflation rates. Visitors to Budapest will thus need to buy some Hungarian forints (HUF). We found that credit cards worked for most transactions, so $50 in HUF will probably suffice for a short visit. Public transportation (metro and trams) is good and cheap, particularly with 24-hour cards. Otherwise, Bolt taxis are convenient and reasonably priced. The downtown area, near the Danube, is a walker’s delight.