Hiram Bingham, the American explorer who “discovered”* Machu Picchu, did not really know what to expect when he ascended that mountain on July 24, 1911. Based on tips provided by locals, he hoped to see some Inca ruins, but anticipated finding a few stone houses, at most.

On the way up, Bingham and his two companions encountered some farmers who cultivated a few of the old Inca terraces on the site. One of them agreed to send his 11 year-old son, Pablito, to show Bingham the way. “Then we walked along a path to a clearing where the Indians had planted a small vegetable garden,” he wrote later. “Suddenly, I found myself confronted with the walls of ruined houses built of the finest quality Inca stone work … hiding in bamboo thickets and tangled fines, appeared here and there walls of white granite carefully cut and exquisitely fitted together.”

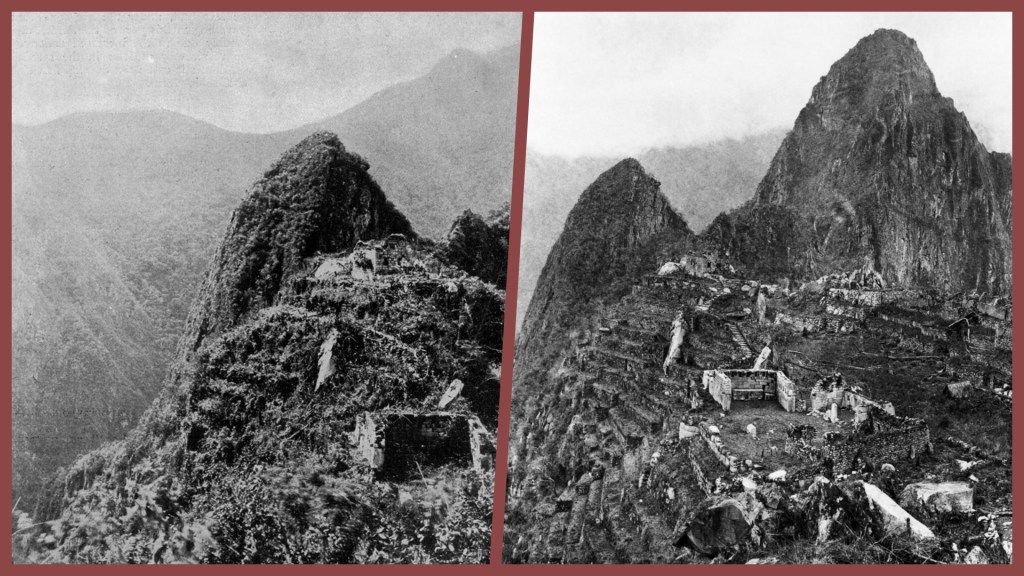

Bingham suspected that he was looking at a major Inca site. But the area was so overgrown that it wasn’t until he was able to return the following year, with a larger scientific expedition and local labor to clear the ground, that he could ascertain the full extent of what soon came to be recognised as one of the greatest archaeological finds of the 20th century. Not bad for a 35 year-old assistant professor of South American history at Yale University!

Bina and I got a similar sense of Machu Picchu unveiling itself during our visit on April 11, 2025.

We had woken that morning in a somber mood. Looking out the window of our hotel in Aguas Calientes at 5:30 a.m., we saw drizzle and overcast skies, just as the Weather Channel had predicted over the last few days. And unhappily for us, this morning represented our only chance to see Machu Picchu, since online tickets for the park entrance were now entirely sold out for the next two months.

Our last hope, as we went downstairs for breakfast, was for the rain to ease off. The forecast anticipated a wet morning until at least noon, but our guide Abraham, whom we met in the lobby at 6:30, said conditions could shift quickly. Despite being nestled in the high Andes, Machu Picchu is near enough to the Amazon rain forest to feature a changeable, semi-tropical climate.

The drizzle had lifted by the time we walked to the bus stop, a few blocks away, but resumed when we disembarked at the park entrance. This spurred us to pull out our rain ponchos and umbrella — the latter being promptly confiscated by a guard at the gate. The numerous restrictions imposed on tourists to Machu Picchu include no umbrellas, no selfie sticks or camera tripods and no bathroom break inside the park (!).

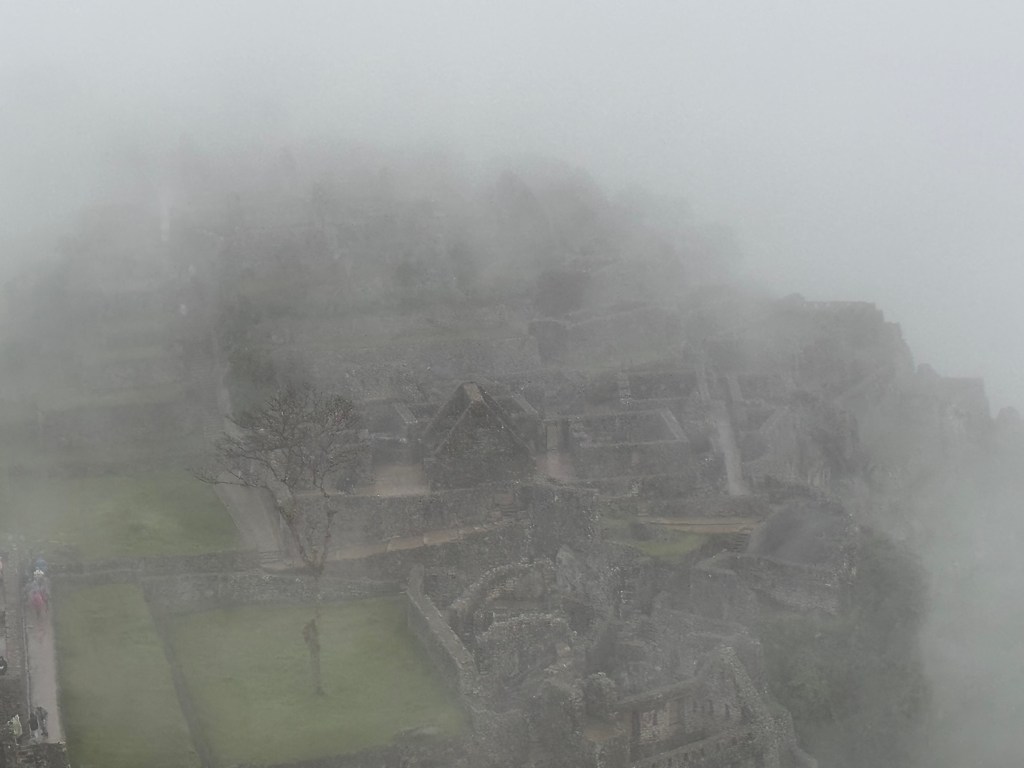

And now we were wrapped in fog. Is this Scotland? When we reached the terrace below the so-called “Guardian’s House” structure, we could see nothing beyond the curtain of white vapor.

Now we stood in the cold drizzle, with about a hundred other tourists, water dribbling down our ponchos, waiting for something to change. It took about 20 minutes but the crowd suddenly began to stir. We rushed to the terrace edge to watch the clouds, ever so tentatively, begin to part.

This parting of the cloud veil coincided — perfect timing! — with a dwindling of the precipitation, enabling us to move about the ruins for the next three hours with only intermittent bouts of drizzle or mist. Thank you Lord! And so, what were we actually looking at?

Bingham had entitled his most famous book Lost City of the Incas — romantic, but not quite accurate. That’s because Machu Picchu housed less than 800 people, hardly city-size. It can more appropriately be described as a vacation palace, or royal estate. Scholars believe it was built in the 15th century as a summer retreat for the emperor Pachacutec and his family to enjoy some time away from the Inca capital in Cusco.

Most of the houses we saw sprawling down the hillside likely belonged to the emperor’s court staff and officials and workers who maintained the place when he wasn’t in residence. The largest structures are temples and what’s left of the royal palace.

You can easily tell the difference between the royal and common structures by the quality of the stonework. Imperial Inca construction, of the kind that first excited Bingham, incorporates smooth and precisely cut stone boulders inserted into place without any use of masonry, in comparison to the rough stones and mortar used in non-royal buildings.

Like all major Inca sites, Machu Picchu is divided into two areas, for habitation and agriculture. The trail into the park begins at the agricultural terraces (hundreds of them, back in the day), where farmers grew the maize and possibly potatoes needed to feed the imperial family. After entering the park at the terraces, we passed through the royal gate to stroll among the temples, palaces and houses.

This royal gate served as the only way commoners could enter the citadel. Our guide Abraham pointed to some some knobs carved out of the stone blocks where guards could secure a wooden door screen to keep out intruders. The citadel wall at this point is also fronted by a dry moat to hinder any attacking force.

Continuing on into the complex, we stopped at the Temple of the Three Windows, distinguished by its three trapezoidal windows in a perfect line, looking out over the valley. Scholars still debate the purpose of this building — perhaps it was used for religious rituals or astronomical observations. In any case, the beauty of the stonework captured our attention.

Other notable structures in the citadel include the Torreon, or Temple of the Sun, notable for its semi-circular shape, and the Sacred Plaza, which features a temple believed by some to have been dedicated to Wiracocha, the Inca god credited with creating the universe.

Unfortunately, because of the absence of written records — from either Inca or Spanish sources — we will never know for sure how these various structures were utilized. Most of the names we use today for these buildings came from Bingham — a history professor, not an archaeologist — who made the best guesses he could at the time.

Some of Bingham’s interpretations are disputed today. In one structure, now known as “The Hall of the Water Mirrors,” Bingham found two circular indented discs carved into the stone floor that he assumed to be grinding stones, probably used for making maize flour. He even took a photo of Pablito making grinding motions with a rock.

Later scholars, noticing that the building had no roof, surmised that these discs actually served as mirrors for astrological calculations. When filled with water, they reflect the image of the sun, moon and stars, which the Incas associated with the movement of their gods in the sky. Again, with the lack of records, we can’t know for sure.

You might say that this lack of precise knowledge actually enhances the appeal of Machu Picchu for modern visitors because they can fill in the blanks for themselves. The Incas were big into astrology and nature-based spirituality, so the site attracts lots of like-minded folk seeking out the “energy” emanating from the place, particularly when the sun lines up in certain crevices at certain times.

Who knows? But as Bina and I can testify, you can’t help but walk about the transcendent beauty of Machu Picchu stunned by awe and wonder. As a bucket list trip, this place absolutely hits the mark.

*For convenience, we typically say Hiram Bingham “discovered” Machu Picchu, but that statement needs hedging. The Incas did abandon the site in the 16th century, to keep it hidden from the Spanish invaders, and seem to have forgotten it over time. It wasn’t until the early years of the 20th century, nearly 400 years later, that locals involved with farming or mining in the area became aware of the ruins. Bingham himself reached Machu Picchu by following up on their tips and encountered three families cultivating terraces on the site (using unregistered land to avoid taxes). While poking around at the Temple of the Three Windows, he also found a name and date etched in charcoal on a rock: “A. Lizárraga 1902.” This could be traced to Agustín Lizárraga Ruiz, a local farmer who arrived there nine years before Bingham, looking for good agricultural land. Unquestionably, then, Peruvians had already re-discovered Machu Picchu before 1911; Bingham was smart enough to publicize the discovery and initiate the first scientific investigations.

As Bingham himself said, in a private letter sent to a friend in 1922:

“I suppose that in the same sense of the word as it is used in the expression ‘Columbus discovered America,’ it is fair to say that I discovered Machu Picchu. The Norsemen and the French fishermen undoubtedly visited North America long before Columbus crossed the Atlantic. On the other hand, it was Columbus who made America known to the civilized world. In the same sense of the word, I ‘discovered’ Machu Picchu …”