Such is the beauty and majesty of Machu Picchu that tourists can be forgiven for believing that the site represents the height of Incan civilization. Yet, in the scale of Incan building achievements, Machu Picchu ranked below the first tier.

Machu Picchu stands out today because it survived relatively intact — never found by the Spaniards. But had you arrived in Peru with the Spanish in the 16th century, other locations would have riveted your attention, most notably the capital city of Cusco, where the emperors built their main palaces and temples with walls plated in gold. Most of that Inca heritage was looted and destroyed following the Spanish conquest in 1533. But impressive ruins remain in Cusco, including Sacsayhuamán, the royal fortress, and Coricancha, the Temple of the Sun.

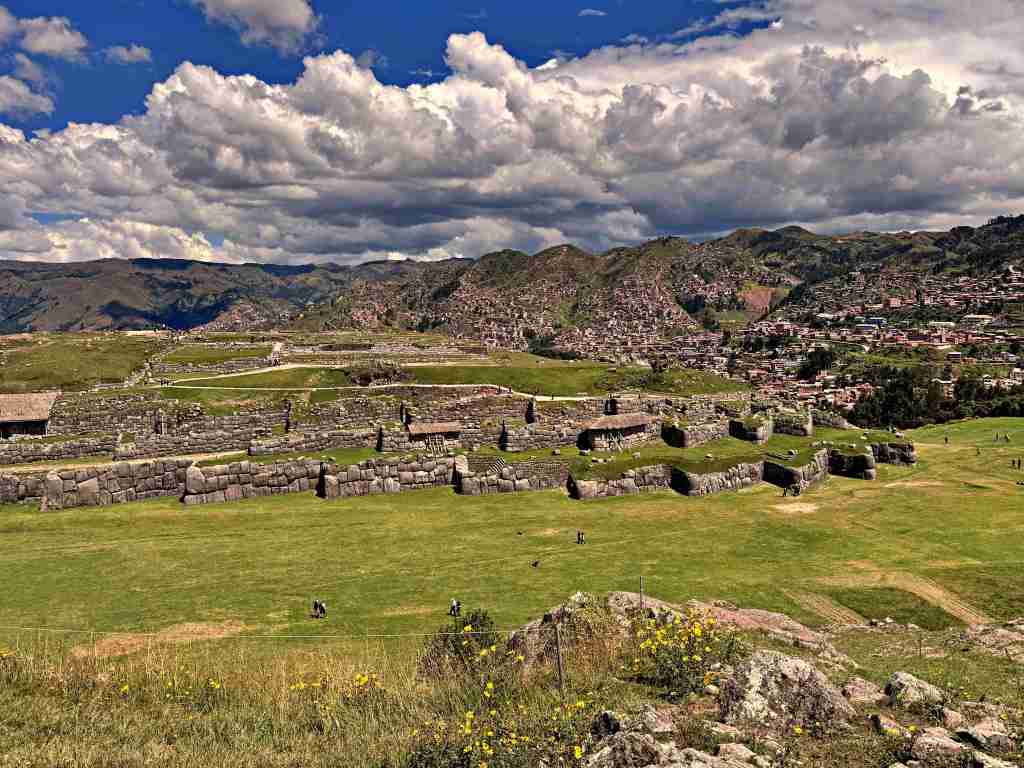

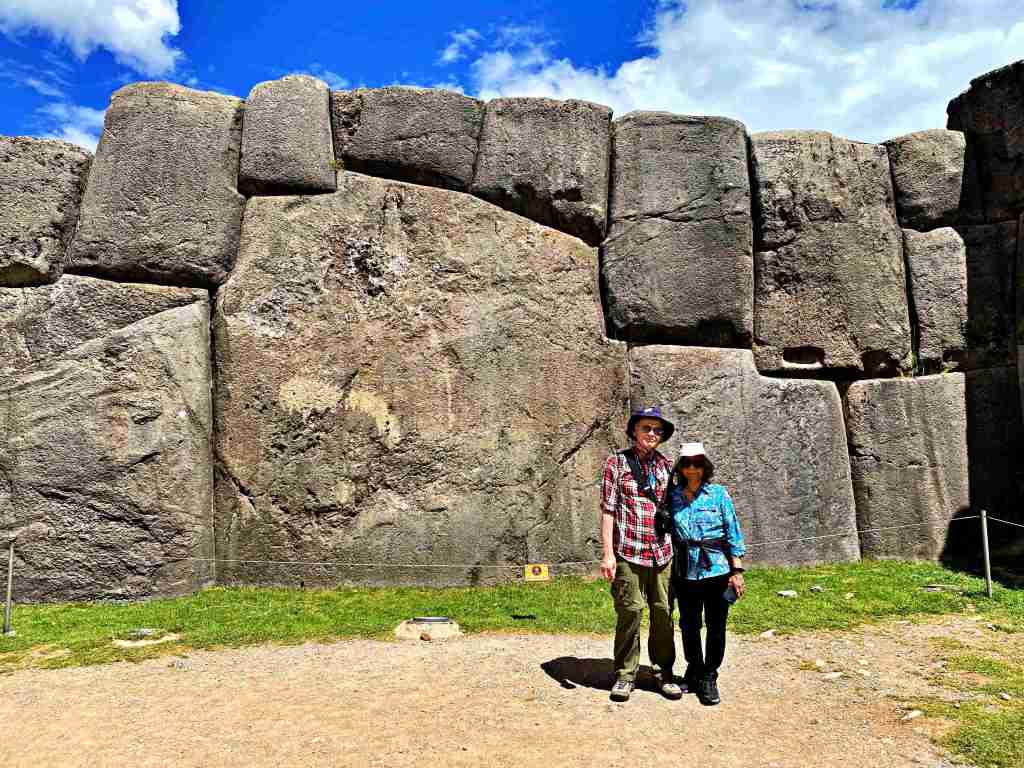

Even in its current ruined state, Sacsayhuamán is monumental: a walled complex covering 7,400 acres (3,000 hectares) sprawling on a plateau overlooking modern Cusco. Inca builders transported enormous stones to the site, one weighing 125 tons, trimming and polishing them to fit into the walls.

We see only the foundations today. The Spanish dismantled most of Sacsayhuamán to provide material for their own buildings in Cusco. “There is indeed not a house in the city that has not been made of this stone, or at least the houses built by the Spaniards,” wrote a Spanish chronicler.

The Calle Loreto, a lane within downtown Cusco itself, connecting the Plaza des Armas with the Coricancha, provides a perfect example of Spanish walls built on Incan foundations, which were always of much better quality.

The relative inferiority of Spanish construction, in fact, is the reason we can appreciate the Temple of the Sun today. During a major earthquake in 1950, the Dominican convent built on top of the Coricancha partially collapsed, revealing previously hidden Inca remains. The Peruvian government agreed to help the Dominicans rebuild their convent in exchange for turning part of the site into a museum.

Just a little north of Cusco is the Sacred Valley itself, which follows the course of the Urubamba River from Pisac to Machu Picchu. The Incas gave the fertile valley that name because they considered it a gift from Pachamama, their earth goddess. They also viewed the Urubamba River as a symbol of the sacred union between earth and water.

For two days, our guide Abraham escorted us around the Sacred Valley in a black Hyundai van driven by a young man named Willy. We visited major Inca sites at Pisac, Chinchero and Ollantaytambo, the latter town being the location of our hotel and the departure point for the tourist train to Machu Picchu 27 miles (44 km) away.

Like Machu Picchu, Ollantaytambo was a royal estate built in the 15th century by Pachacuti, the “Alexander the Great” of the Incas, who expanded the empire to its greatest extent. It’s also noteworthy as the last Incan stronghold in the Sacred Valley to resist the Spanish before Emperor Manco Inca fled the Andes to the sweltering Amazon basin region in 1537. The first thing you notice when arriving at the archaeological site is an array of 17 large terraces, which you must climb, via stair steps on the sides, to reach the citadel and temples.

Resting every five terraces to catch our breath, we ascended to the top, from where we enjoyed a spectacular view of the modern town of Ollantaytambo and the surrounding mountain valleys. The summit itself features a never-completed sun temple notable for its “Wall of the Six Monoliths,” a joining of six stone slabs each weighing about 50 tons. Kudos to the Inca builders for managing to drag these stones up the hill from a nearby quarry!

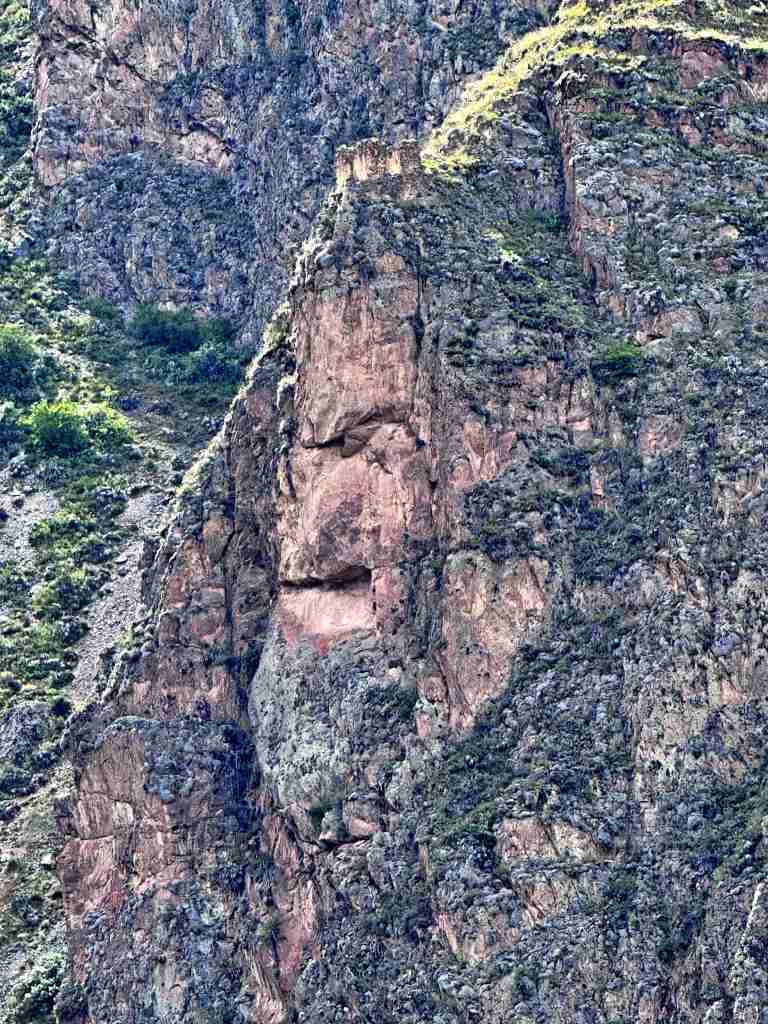

One odd sight from the citadel is what seems to be a carving of the face of a bearded man on a nearby mountain. Tourist guides, including our Abraham, like to tell visitors that this represents the main Inca god known as Wiracocha. Later research on Google revealed, however, that this interpretation comes from a popular book about Inca spirituality published in the 1990s rather than current scholarly opinion.

Pisac is at the other end of the Sacred Valley from Ollantaytambo. It was also built by Pachacuti, and has a walled citadel, a temple complex, agricultural terraces and houses for both rich and poor. One challenge for visitors is that the ruins are spread over both sides of a ridge, requiring between three to four hours of hiking to reach them all. Given our tight schedule that morning, we contented ourselves with some photo taking from the lower slopes.

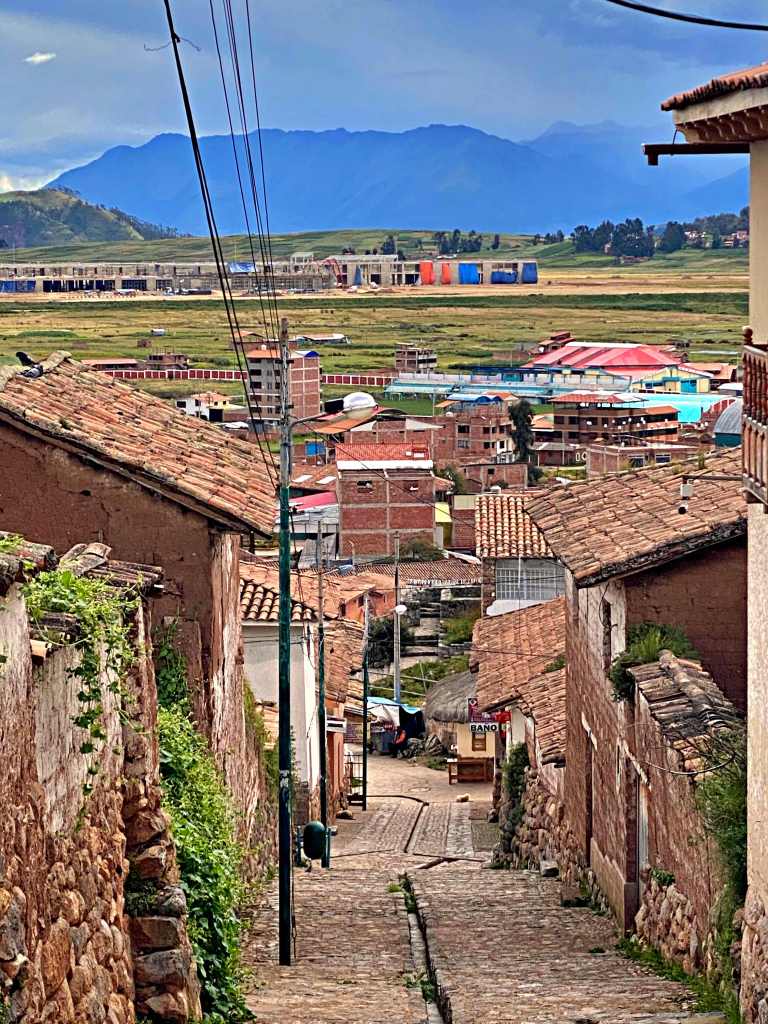

Located roughly midway between Ollantaytambo and Pisac is Chinchero, which features less extensive Inca ruins than the other two but in a more authentic Peruvian setting, with few restaurants or tourist lodgings and some lanes too narrow for cars.

We parked about 10 minutes away from the archaeological site to walk to the park, noticing along the way small ceramic bulls sitting atop some houses. Known as Toritos de Pucará (“bulls of Pucará,” named for another town in Peru), Abraham told us that they are put there — often fronting a cross — to bring protection, fertility, and prosperity to the home.

The Inca site itself is underwhelming in that much of it lies underneath the colonial era church, known as the Nuestra Señora de la Natividad. It’s the same old story: the Spanish levelled the Inca structures at Chinchero and used the stones for their own buildings. The structure directly under the church is believed to be the palace of Tupac Inca Yapanqui, one of the sons of Pachacuti.

The government park service, thankfully, has excavated and restored much of the land adjoining the church to expose more detail in the Inca foundations, which covered a total of 43 hectares (106 acres), including terraces, paths, water channels and temples.

Following our visit to the Inca site, we dropped by one of town’s textile shops, where you can watch women in traditional costume weaving shawls, blankets, carpets and runners using old-style looms and authentic vegetable dyes. Bina bought a shawl and enjoyed feeding some llamas and alpacas kept in a corral there.

Chinchero’s status as one of the most authentic Indian communities left in the Sacred Valley may not last long. Construction is currently underway for a new international airport on the plain right next door. With a capacity for five million passengers annually, this will divert tourist traffic away from Cusco into the Sacred Valley itself, which is already experiencing a building boom in vacation rentals and hotels.

Turning the Sacred Valley into one big tourist strip would be a shame because much of it remains unspoiled, with lofty mountains framing green meadows. Inca ruins aside, a visit here can be worthwhile just for the scenic beauty.

Travel Tips: Other interesting sights to visit in the Sacred Valley, if you have time, are the salt pans of Maras and the Inca terraces at Moray.

The former consists of 6,000 small ponds carved out of a hillside fed by underground channels from a salt water spring. The ponds are owned by local families belonging to a cooperative who harvest the salt with rakes and shovels after closing the channels and letting the water evaporate. Being familiar with coastal salt pans in the Portuguese Algarve, Bina and I were startled to find a similar operation in the Andean Mountains.

Likewise intriguing are the Moray terraces, which is a big hole in the ground (40 yards deep) in the shape of an inverted cone, with concentric terraces climbing the sides. The prevalent theory is that the Incas used the terraces as an outdoor greenhouse to test their crop seeds in varying microclimates, since the temperature at the rim is 27 degrees F. cooler than at the bottom. A recent study challenges this view, however, arguing that the site served religious/ceremonial purposes.

Oddly enough, one of the most exclusive restaurants in Peru overlooks the site. All the food served at the restaurant known as MIL Centro is sourced locally in the surrounding mountains and modelled on traditional recipes. If you want authentic Peruvian cuisine, this is it. But with lunch costing roughly $360 a person, we had to pass.